April 1, 2014 report

Researchers gain new insight on language development

(Medical Xpress)—Two new studies appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveal what appear to be innate language preferences. In one study, Jacques Mehler of the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati in Trieste, Italy and his colleagues discovered that newborns distinguish syllables commonly found in different languages from rare syllables. A study by Jennifer Culbertson of George Mason Unity in Fairfax, Virginia and David Adger of Queen Mary University of London shows that people have an innate preference for ordering words based on their meanings.

Mehler and his team had 72 newborns, between two and five days old, listen to recordings of nonsense syllables spoken by native Russian speakers. The infants heard syllables like "blif", which are common in many different languages, as well as syllables like "lbif" and "bdif," which are much less common. When the researchers studied blood flow in the newborns' brains, they found that the newborns reacted differently to the common syllables than to the uncommon ones.

Frequently heard syllables like "blif" obey the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP), which provides rules for ordering the sounds in a syllable. Syllables like "blif" follow the SSP, while syllables like "lbif" and "bdif" violate it. The study suggests that the SSP is innate rather than learned.

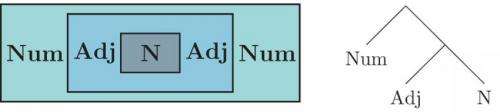

Culbertson and Adger wanted to compare two theories about how people learn rules about word order. One theory says we memorize superficial rules. For example we say "four blue cars, " rather than "blue four cars" because we know, from listening to others, that "four" is supposed to come before "blue," which is supposed to come before "cars." The second theory says we have an innate tendency to place words together based on how their meanings relate to each other. "Blue" modifies the meaning of "cars," so the word "blue" seems closer to the word "cars" than the word "four" does.

The team told volunteers they wold be learning an artificial language similar to English. This language contained English words, but its word order was different from English word order. At first, the subjects learned two word phrases like "town one" and "wagon full." Later, they had to choose one of four possible ways to translate three word English phrases, like "four blue cars" or "two young women," into the new language. Most of the time, the subjects preferred phrases like "cars blue four" over phrases like "cars four blue." The preference for keeping "blue" and "cars" together, rather than placing "four" before "blue," as in the English phrase, provides evidence of an innate sense of language structure based on word meaning.

More information: 1. Language learners privilege structured meaning over surface frequency, PNAS, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320525111

Abstract

Although it is widely agreed that learning the syntax of natural languages involves acquiring structure-dependent rules, recent work on acquisition has nevertheless attempted to characterize the outcome of learning primarily in terms of statistical generalizations about surface distributional information. In this paper we investigate whether surface statistical knowledge or structural knowledge of English is used to infer properties of a novel language under conditions of impoverished input. We expose learners to artificial-language patterns that are equally consistent with two possible underlying grammars—one more similar to English in terms of the linear ordering of words, the other more similar on abstract structural grounds. We show that learners' grammatical inferences overwhelmingly favor structural similarity over preservation of superficial order. Importantly, the relevant shared structure can be characterized in terms of a universal preference for isomorphism in the mapping from meanings to utterances. Whereas previous empirical support for this universal has been based entirely on data from cross-linguistic language samples, our results suggest it may reflect a deep property of the human cognitive system—a property that, together with other structure-sensitive principles, constrains the acquisition of linguistic knowledge.

2. Language universals at birth, PNAS, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1318261111

Abstract

The evolution of human languages is driven both by primitive biases present in the human sensorimotor systems and by cultural transmission among speakers. However, whether the design of the language faculty is further shaped by linguistic biological biases remains controversial. To address this question, we used near-infrared spectroscopy to examine whether the brain activity of neonates is sensitive to a putatively universal phonological constraint. Across languages, syllables like blif are preferred to both lbif and bdif. Newborn infants (2–5 d old) listening to these three types of syllables displayed distinct hemodynamic responses in temporal-perisylvian areas of their left hemisphere. Moreover, the oxyhemoglobin concentration changes elicited by a syllable type mirrored both the degree of its preference across languages and behavioral linguistic preferences documented experimentally in adulthood. These findings suggest that humans possess early, experience-independent, linguistic biases concerning syllable structure that shape language perception and acquisition.

© 2014 Phys.org