Long distance calls by sugar molecules

All our cells wear a coat of sugar molecules, so-called glycans. ETH Zurich and Empa researchers have now discovered that glycans rearrange water molecules over long distances. This may have an effect on how cells sense each other.

Glycoproteins are an essential part of our body: These sugar-protein hybrid molecules are what makes the protective mucus that lines our lungs and stomach. They are also part of the fluid that lubricates our joints, the synovial fluid, and cover all our cells, with the sugar parts, the glycans, sticking out like a tiny forest of antennae. Researchers in the Laboratory for Surface Science and Technology at ETH Zurich and the Laboratories of Nanoscale Materials Science of Empa have identified a surprising effect that glycans have on the water molecules that surround them.

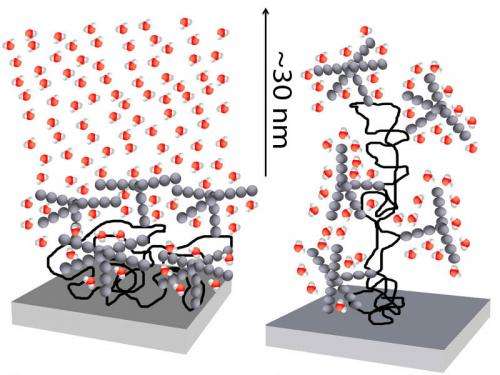

Nicholas Spencer, professor for Surface Science and Technology in the Department of Materials and Rowena Crockett at the Empa, along with their colleagues, discovered that glycans order the otherwise random network of water molecules above them. Compared to the size of a water molecule which is only about 0.3 nanometres, the distance over which glycans arrange water molecules is huge: The maximum distance at which this effect can be detected is in the range of tens of nanometres—far beyond any expected boundary values. "Since the membranes of our cells are covered in glycans, this may be a way that cells can communicate with each other across water", hypothesises Spencer.

Long-range effect on water structure

To imitate the configuration that glycans acquire on cell surfaces, Rosa Espinosa-Marzal, co-worker of Spencer, coated a mica surface with a single layer of a well-characterised glycoprotein. While the protein part attached itself to the mica surface, the glycans pointed away from the surface. She then gradually brought a bare mica surface towards the glycoprotein-covered surface, with water between them, and measured the continually increasing repulsive force between them. "To our surprise, there were jumps in this continuous increase in repulsion", explains Espinosa-Marzal, "as if we were squeezing out whole sheets of water and thus relieving the repulsive pressure for a moment."

These jumps are caused by the glycans rearranging the network of water molecules above them into clusters or layers. This rearranging effect completely disappeared when the researchers added a chemical to unfold the configuration of the glycoproteins, indicating that the orientation of the glycans is crucial to produce this layering effect on the water molecules above them.

This long-range influence of glycans on water may explain why glycoproteins help synovial fluid lubricate our joints so well. Also, the glycan coat that our cells – but also bacteria or fungi – wear, can be recognised for instance by our immune system or by receptors, sensors that are part of another cell. By means of their water-clustering properties, glycans may produce a sort of shield around themselves that affects how well a receptor can recognise them. It remains to be seen if cells could indeed communicate across water by means of their glycan coat but it may very well affect the way in which two cells can sense each other's presence.

More information: Espinosa-Marzal R.M., Fontani G., Reusch F.B., Roba M., Spencer N.D., Crockett R.: Sugars communicate through water: oriented glycans induce water structuring. Biophys J 104/12, 2013, dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.017

Provided by ETH Zurich