How we know where we are

Knowing where we are and remembering routes that we've walked are crucial skills for our everyday life. In order to identify neural mechanisms of spatial navigation, RUB researchers headed by Prof Dr Nikolai Axmacher, together with colleagues from Bonn, analysed the relevant processes with the aid of an electroencephalography (EEG) monitored directly in the brain. Thus, they identified the neural signature during learning and remembering of specific spatial locations. Their report was published in the current edition of Current Biology.

Distributed and local activity patterns in spatial navigation

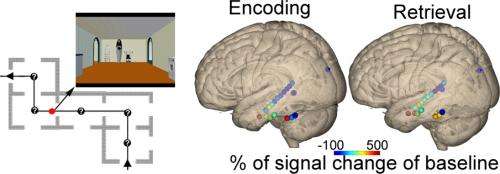

How do we know where we are at any given moment? How do we remember routes that we've walked? Spatial navigation has long been a subject of psychological and brain research. "It is likely that there is more than one spatial navigation mechanism; rather, the brain uses different 'codes' to memorise locations," says Nikolai Axmacher. In their current study, the RUB scientists and their colleagues at the Department for Epileptology in Bonn analysed distributed and local activity patterns during spatial navigation.

Memorising paths in virtual houses

Ten epileptic patients participated in the study; EEG electrodes were implanted directly in their brains as part of a surgical procedure. During EEG monitoring, the patients were asked to memorise paths through virtual houses and to remember those paths afterwards. The researchers thus successfully identified the neuronal signature during learning and remembering of specific spatial locations. "Distributed and local activity patterns appear to be related: the brain regions that contributed to distributed spatial representations also contained fairly precise information on a local scale," explains Nikolai Axmacher. "The accuracy of spatial representations was rather variable; interestingly, more reliable representations occurred if the brain's overall activity in a rapid frequency range was comparatively low." These results suggest that spatial navigation is particularly successful if other, irrelevant activities can be suppressed. "Just how important the question of the neuronal basis of spatial navigation is became apparent last year," elaborates the researcher: "All three Nobel Prizes in Medicine were awarded to scientists who conducted research in this field."

More information: Zhang et al.: "Gamma power reductions accompany stimulus-specific representations of dynamic events." In: Current Biology, February 12, 2015, dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.011