Understanding chromatin's cancer connection

When scientists finished decoding the human genome in 2003, they thought the findings would help us better understand diseases, discover genetic mutations linked to cancer, and lead to the design of smarter medicine. Now it's 13 years later, and not all of these ideas have not yet come to fruition.

"We thought that understanding genes would answer all of our questions," said Northwestern Engineering's Vadim Backman. "But it's not that simple."

It turns out that genes are just one piece of a much larger puzzle. To help put this puzzle together, Backman has developed a new way to image chromatin, a complex of macromolecules—including DNA, RNA, and proteins—within living cells that house genetic information and determines which genes get expressed.

"If you think of cellular systems as computers, then genes are the hardware, and chromatin is the software," said Backman, the Walter Dill Scott Professor of Engineering at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering.

Chromatin's organization plays a major role in many molecular processes, including DNA transcription, replication, and repair. The structures within chromatin that regulate these processes span from nucleosomal (10 nanometers) to chromosomal (longer than 200 nanometers) length scales.

Little is known about chromatin's dynamics between these length scales due to lack of imaging techniques. Because they require toxic fluorescent dyes to enhance contrast, previous techniques could not image chromatin in living cells without killing or perturbing the cells. Understanding this missing length scale is crucial, however, because it is the exact area where chromatin undergoes a transformation when cancer is formed.

"Changes in chromatin's structure have been linked to the regulation in genes often implicated in cancer," Backman said. "The organization of chromatin correlates both with the formation of tumors and their invasiveness. We want to understand how chromatin regulates these genes."

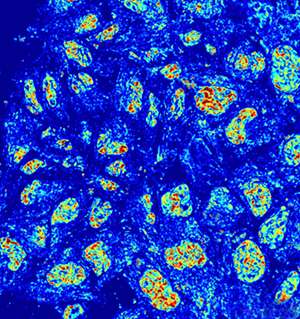

Backman's new imaging technique allows researchers to peer inside of chromatin at the missing, mysterious length scale (20-200 nanometers). Not only is the technique label-free, allowing researchers to study chromatin within unharmed, living cells, but it does so with high-throughput and at very low cost.

Supported by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Chicago Biomedical Consortium, the research is described online on October 4 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Luay Almassalha, Greta Bauer, John Chandler, and Scott Gladstein, all graduate students in Backman's laboratory, served as co-first authors on the paper. Northwestern Engineering's Igal Szleifer, the Christine Enroth-Cugell Professor of Biomedical Engineering, and Hariharan Subramanian, research assistant professor in biomedical engineering, also contributed to the work.

"Now we can look at live, healthy cells unperturbed and see their dynamic processes," Almassalha said. "We can see how the chromatin is organized and how it responds to stimuli, such as drug treatments."

Called live cell Partial Wave Spectroscopic (PWS) microscopy, the technique detects chromatin by using scattered light. Particles smaller than the diffraction limit of light cannot be visualized but their presence and organization can be sensed by analyzing the light they scatter. The approach can measure the nano-architecture in live cells within seconds, opening the door for large-scale screens. Researchers can run high-throughput screens on thousands of compounds and drugs, for example, and watch how they affect cells in real time.

"We know that chromatin is a major player in complex diseases," Backman said. "We just haven't had the techniques to study it. Now we can watch and record these dynamic processes as they unfold."

More information: Label-free imaging of the native, living cellular nanoarchitecture using partial-wave spectroscopic microscopy, Luay M. Almassalha, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1608198113 , www.pnas.org/content/early/201 … 0/03/1608198113.full

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Northwestern University