Researchers bring new insight into Chediak-Higashi syndrome, a devastating genetic disease

A team of researchers from the National Institutes of Health and University of Manchester have uncovered new insights into a rare genetic disease, with less than 500 cases of the disease on record, which devastates the lives of children.

Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS) is a complex disease, exhibiting very diversified symptoms, including predisposition to bleeding, a wide range of neurological issues, and dysregulated immune responses so that they are unable to fight infections which would normally be easily dealt with.

Unfortunately, in the majority of cases, people with CHS develop a severe and fatal hyperinflammatory condition. One feature of CHS patient's is that a population of white blood cells, known as Natural Killer (NK) cells are unable to function properly.

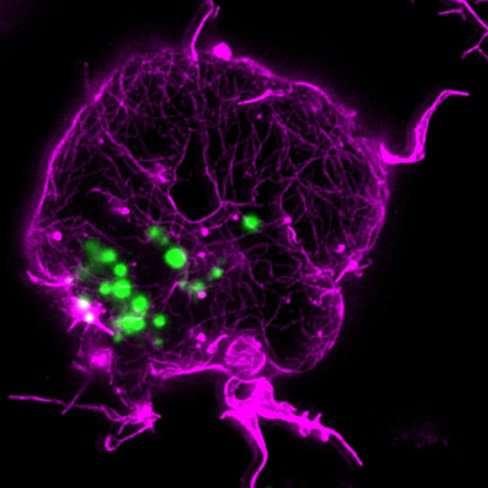

Normally, 'NK cells' recognize and kill aberrant cells, like cancer cells or virus-infected cells, by secreting bags of toxic enzymes, called lytic granules, into the diseased cells. However, this does not happen in the case of CHS; people with CHS have larger-than-usual bags of these enzymes which then cannot exit the immune cell properly.

The team – which includes Professor Daniel Davis from The University of Manchester – found that the defects in in CHS immune cells are related to a mechanical barrier, the cell's cytoskeleton, which seems to prevent the immune cells' ability to kill diseased cells.

In order to uncover the underlying cause for the defective function of NK cells in CHS, they generated a human cell line model of the disease, using modern gene editing techniques.

With the model and super-resolution microscopy, they demonstrated that CHS NK cells have the ability to respond normally to different stimuli, but can't secrete their lytic granules, because they are simply too big to pass through the barrier of the cell's cytoskeleton.

Professor Davis said: "My research team and I have been using microscopes to watch how immune cells kill diseased cells for many years. From what we and others have learnt, we can now see how medicines might be able aid the process. Working with researchers at the NIH, we found that the activity of CHS NK cells could be partially restored with drugs that open up an internal barrier in cells, the cell's cytoskeleton.

"The problem was that the meshwork of actin protein that underlines the cell membrane is too dense to allow these giant lytic granules out of the cell, resulting in defective CHS NK cell function.

"Importantly, we found that decreasing the actin density, or the size of lytic granules, restores the ability of CHS NK cells to kill target cells.

"Thus, restoration of white blood cell function in CHS could be possible, and a major factor limiting the release of enlarged lytic granules could be a novel target for drug development."

Davis added: "Our findings provide a new and important insight into pathology of this rare genetic disease.

"Broader than this, this is one example of how immunologists are beginning to harness the power of the immune system to tackle all sorts of diseases, from cancer to autoimmune disease.

"Restoring the function of white blood cells in CHS might have an important impact for the patients' welfare, as it could extend the period of time CHS patients can wait for a bone marrow transplant that is now the only way to prevent the development of a fatal hyperinflammatory condition that occurs in many people with CHS."

The researchers' findings suggest the potential to negate this problem and restore proper immune cell function. The research is published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Professor Davis is author of popular level books about the immune system, 'The Compatibility Gene' and the forthcoming 'The Beautiful Cure'.

He is Director for Research at the University's Manchester Collaborative Centre for Inflammation Research, which also announces today £2m of investment from GlaxoSmithKline.

The MCCIR, established in 2012, is unique collaboration which has established a world-leading translational centre for inflammatory diseases. It employs 86 scientists and a cumulative grant research budget of £43M.

The cash will fund 11 additional projects in PhD and postdoctoral level in the areas COPD, kidney injury, asthma, IBD, complement function and super-resolution microscopy

Professor Tracy Hussell, Director, MCCIR said: "Industry has a pivotal role to play in discovery science and it is crucial that we share early stage research ideas and tools to enable us to tackle new ideas and approaches that could benefit all.

"This reinvestment by GSK is an endorsement of that philosophy and since our collaboration, we have won a significant amount of competitive peer reviewed funding."

Malcolm Skingle, Director of Academic Liaison, GSK said: "Collaboration with academic researchers is vital to progress scientific understanding and enable development of innovative new medicines.

"We are delighted to continue to support UK based research efforts through our continued collaboration with the MCCIR academic scientists'."

The paper, "An actin cytoskeletal barrier inhibits lytic granule release from Natural Killer cells in Chediak-Higashi syndrome," is published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

More information: Aleksandra Gil-Krzewska et al. An actin cytoskeletal barrier inhibits lytic granule release from Natural Killer cells in Chediak-Higashi syndrome, Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2017). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.040