Researchers unearth secret tunnels between the skull and the brain

Bone marrow, the spongy tissue inside most of our bones, produces red blood cells as well as immune cells that help fight off infections and heal injuries. According to a new study of mice and humans, tiny tunnels run from skull bone marrow to the lining of the brain and may provide a direct route for immune cells responding to injuries caused by stroke and other brain disorders. The study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and published in Nature Neuroscience.

"We always thought that immune cells from our arms and legs traveled via blood to damaged brain tissue. These findings suggest that immune cells may instead be taking a shortcut to rapidly arrive at areas of inflammation," said Francesca Bosetti, Ph.D., program director at the NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), which provided funding for the study. "Inflammation plays a critical role in many brain disorders and it is possible that the newly described channels may be important in a number of conditions. The discovery of these channels opens up many new avenues of research."

Using state-of-the-art tools and cell-specific dyes in mice, Matthias Nahrendorf, M.D., Ph.D., professor at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues were able to distinguish whether immune cells traveling to brain tissue damaged by stroke or meningitis, came from bone marrow in the skull or the tibia, a large legbone. In this study, the researchers focused on neutrophils, a particular type of immune cell, which are among the first to arrive at an injury site.

Results in mouse brains showed that during stroke, the skull is more likely to supply neutrophils to the injured tissue than the tibia. In contrast, following a heart attack, the skull and tibia provided similar numbers of neutrophils to the heart, which is far from both of those areas.

Dr. Nahrendorf's group also observed that six hours after stroke, there were fewer neutrophils in the skull bone marrow than in the tibia bone marrow, suggesting that the skull marrow released many more cells to the injury site. These findings indicate that bone marrow throughout the body does not uniformly contribute immune cells to help injured or infected tissue and suggests that the injured brain and skull bone marrow may "communicate" in some way that results in a direct response from adjacent leukocytes.

Dr. Nahrendorf's team found that differences in bone marrow activity during inflammation may be determined by stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), a molecule that keeps immune cells in the bone marrow. When levels of SDF-1 decrease, neutrophils are released from marrow. The researchers observed levels of SDF-1 decreasing six hours after stroke, but only in the skull marrow, and not in the tibia. The results suggest that the decrease in levels of SDF-1 may be a response to local tissue damage and alert and mobilize only the bone marrow that is closest to the site of inflammation.

Next, Dr. Nahrendorf and his colleagues wanted to see how the neutrophils were arriving at the injured tissue.

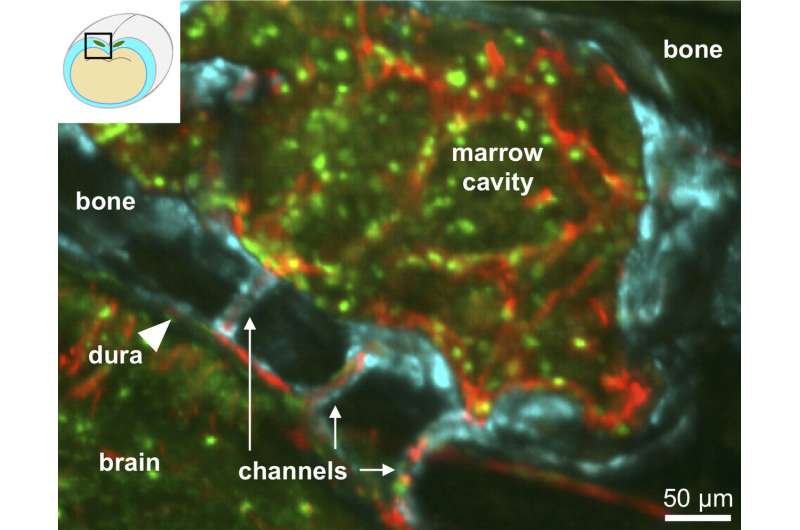

"We started examining the skull very carefully, looking at it from all angles, trying to figure out how neutrophils are getting to the brain," said Dr. Nahrendorf. "Unexpectedly, we discovered tiny channels that connected the marrow directly with the outer lining of the brain."

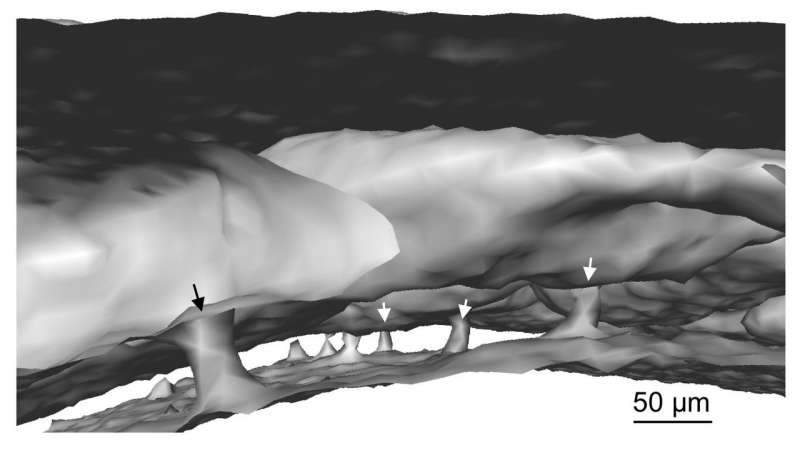

With the help of advanced imaging techniques, the researchers watched neutrophils moving through the channels. Blood normally flowed through the channels from the skull's interior to the bone marrow, but after a stroke, neutrophils were seen moving in the opposite direction to get to damaged tissue.

Dr. Nahrendorf's team detected the channels throughout the skull as well as in the tibia, which led them to search for similar features in the human skull. Detailed imaging of human skull samples obtained from surgery uncovered the presence of the channels. The channels in the human skull were five times larger in diameter compared to those found in mice. In human and mouse skulls, the channels were found in the both in the inner and outer layers of bone.

Future research will seek to identify the other types of cells that travel through the newly discovered tunnels and the role these structures play in health and disease.

More information: Fanny Herisson et al, Direct vascular channels connect skull bone marrow and the brain surface enabling myeloid cell migration, Nature Neuroscience (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-018-0213-2